|

|

|

Agribusiness Review - Vol. 6 - 1998

Paper 10

ISSN 1442-6951

Resource Use Conflicts in A Multi-User Environment:

Land Assignment in the Australian Sugar Industry

Thilak Mallawaarachchi

CSIRO Tropical Agriculture & CRC for Sustainable Sugar Production,

PMB Aitkenvale, Townsville Q 4814, Australia

Ph: 61-7-4753 8640; Fax: 61-7- 4753 8650

An earlier version of this paper was presented to the 42nd Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, University of New England, Armidale, January 19-21, 1998. I thank Professor John Quiggin for providing valuable guidance in this research. Comments made by Malcolm Wegener, Andrew Johnson, Gil Rodriguez and two anonymous reviewers on an earlier draft of this paper are also gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are my own responsibility.

Key words: Sugar Industry, resource management, land-use planning, multiple use, economics, environmental effects

Abstract

The Australian sugar industry has expanded rapidly since 1991. In spite of progressive policy changes, sugar industry remains highly regulated. The land assignment system that governs the industry expansion allocates production quotas. This complex process includes trade-off decisions among economic, environmental and social objectives, and is therefore prone to resource use conflicts. Mutually acceptable solutions to resolve conflicts that surround cane land assignment have important implications for the economic viability of the industry, the ecological integrity of natural resources, and the well being of regional communities.

The assignment system offers ephemeral protection to growers and millers from income instability by barring them from direct competitive pressures. However, the continuing call for reform relates to the associated efficiency costs of regulation, greater demand for potential cane land and growing environmental concerns over expansion. Achieving equity amongst multiple stakeholders has been an issue of conflict and managing the process introduces questions of efficiency. This paper presents a critical review of the cane land assignment system and identifies alternative reform strategies to address the resource allocation issues with least costs to the parties in conflict.

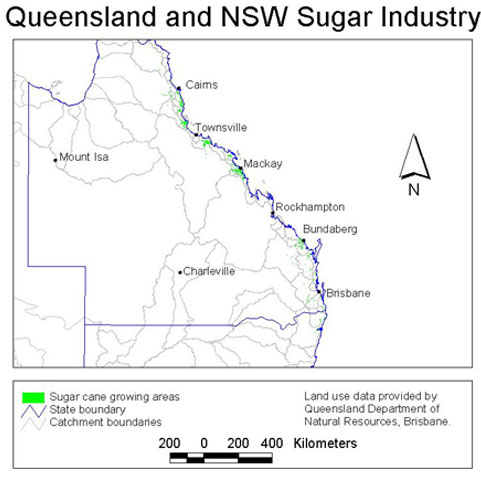

The Australian sugar industry embarked on a rapid expansion phase following changes to regulatory arrangements introduced in the Sugar Industry Act 1991. Figure 1 shows the increase in assigned cane area in Queensland, following this policy change. The Queensland sugar industry dominates sugar production in Australia, supplying about 95 per cent of country's 5 million tonne raw sugar output. Most of Australia's sugarcane is grown on coastal plains and river valleys along 2100 km of the eastern coastal fringe between Mossman in far northern Queensland and Grafton in northern New South Wales (Figure 2) . In 1996 a new sugar mill commenced production in the Ord region of Western Australia, with a potential capacity to produce 70,000 tons of raw sugar.

Sugar industry in Australia has been tightly regulated since 1901 under Commonwealth and State legislative controls and statutes governing sugar marketing and cane growing. Despite considerable changes over recent years towards deregulation and minimal intervention by the Commonwealth, the sugar industry remains highly regulated in 1998, with tight State controls on cane growing, milling and marketing of raw sugar.

Figure 1: Assigned cane area in Queensland

Being a significant natural resource user in a region of diverse economic activity, the sugar industry faces conflicts related to resource use with a range of other interests. Coastal Queensland is undergoing change. Growing sectors such as tourism and recreation, urban infrastructure, public utilities and private life-style seekers are competing for natural resources hitherto primarily being used for agriculture (Johnson et al. , 1997) . Co-location of incompatible uses, such as those favouring natural use as against urban and agricultural development, creates opportunities for conflicts.

In particular, greater community interest in the amenity value of the natural environment, its preservation for future generations and effective involvement in its management brings the sugar industry to the fore-front of community debate and policy focus regarding regional resource allocation.

As a consequence, the sugar industry activities are receiving greater environmental scrutiny by the public, and the sugar industry is taking a tactical interest to safeguard its future. Independent analysis of these issues and responses can strengthen the arguments for broader public interest in times of active policy dialogue.

Figure 2

The geographic location of the Australian Sugar Industry adjacent to an environmental region of national significance (Great Barrier Reef and the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area), predisposes the industry to a high level of environmental compliance. Nevertheless, the industry's recent expansion in Queensland has been associated with a growing number of environmental disputes. The protracted dispute over the protection of an endangered species, the Mahogany Glider (Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, 1995) , and the concerns of environmental interest groups over land allocation decisions by local Cane Assignment Boards are both examples of conflicts between conservation and development. In addition, the growing demand for residential and urban infrastructure developments along the coastal belt is placing economic pressure on cane farms. Hence, the level of interest and the range of stakeholders concerned with the expanding natural resource use in cane growing regions has broadened substantially in recent years.

Queensland sugar cane area reached 492,729 ha in 1997. Industry expansion continues, albeit at a slower phase in many regions. Some estimates suggested that the cane area could reach 590,000 ha by 2003 (Queensland Department of Primary Industries, 1995) . Mary Maher and Associates (1996) and Johnson et al. (1997) identify a range of potential environmental consequences of industry expansion. Furthermore, the economic and infrastructure issues associated with such a high rate of growth can be significant.

The objective of this paper is to analyse the potential economic and environmental trade-offs associated with sugar industry operations and to examine those issues in the context of the sugarcane assignment system. The following discussion focuses on the historical development of the Australian Sugar Industry and the emergence of the cane land assignment system as a key lever of the existing regulatory arrangements. The discussion leads to the nature of challenges facing the industry over the medium term to address the conflicts related to the efficiency costs of regulation, greater demand for cane land and growing environmental concerns over expansion. The paper concludes with some strategies to address the equity and efficiency issues in natural resource allocation amongst multiple stakeholders.

In Queensland, regulations govern almost every aspect of cane growing, milling and marketing of raw sugar (Industry Commission, 1992) . Land on which sugarcane is grown, the mill to which cane is delivered, and the distribution of revenue between cane growers and sugar mills are all controlled by industry regulations. The Queensland Sugar Corporation, a government monopsony, is the sole buyer of all raw sugar produced in the state and is therefore able to market raw sugar as a single-desk seller.

Most existing controls were granted during 1901 to 1939 by the Queensland state government. Importation of sugar and sugar products were made prohibitive by the Commonwealth Government under the Customs Act 1901 .

Queensland government introduced further protection in 1915 as a wartime measure, with the introduction of fixed domestic pricing, and monopsonic acquisition and monopolistic marketing of Queensland raw sugar, under The Sugar Acquisition Act 1915. Since 1923, the Commonwealth and Queensland Governments concluded successive Sugar Agreements. These agreements offered the formal basis for policy dialogue regarding the sugar industry, between the two tiers of government. The Queensland Sugar Board carried out the marketing of sugar produced in both Queensland and the small industry in New South Wales. Commonwealth Government price support continued in the form of an embargo on imports of sugar and its close substitutes. These arrangements helped Australia becoming a net exporter of raw sugar by 1923.

Early growth of the industry led to continued increase in exports. These exports to mainly unprotected markets led to declining grower returns and a consequent push for further controls to safeguard established growing and milling interests. The two pool pricing system incorporating mill peaks was designed to discourage cane growing on unassigned land and to ensure higher returns to established growers. These arrangements were introduced in The Regulation of Sugar Cane Prices Act 1962 (as revised) which established the framework for the operation of Cane Prices Boards and the land assignment system for controlling production. Assignment conditions stipulated that cane was grown only on assigned land and that the growers were required to deliver all cane so grown to a specified mill. Mills in turn were obliged to accept all cane produced on assigned land.

Further controls on industry expansion were introduced after Australia acceded to the first International Sugar Agreement (ISA) in 1977. ISA specified restrictions on export volumes, and as a result, ‘penalty' prices were introduced (growers to receive only $1 per tonne) for sugar produced on unassigned land. Although ISA lapsed in 1984, the controls continued to evolve reflecting the balance between the bargaining strength of the sugar industry and changing national and international economic environment.

While the sugar industry received continued support under state and federal arrangements there have been numerous reviews to determine the level of that support. At one of the periodic reviews of the pricing arrangements in 1970, a formula to establish annual adjustments to domestic sugar price was introduced. This formula was revised in 1979, and thereupon the pricing formula for raw sugar reflected a combination of economic and financial variables that determine the costs of supplying the domestic market.

In 1983, the Industries Assistance Commission (IAC) review of the sugar industry concluded that assistance to the industry should be substantially reduced (McKinnon, 1983) . The report recommended the abolition of the export embargo on sugar; the removal of assignment; the removal of the formula for domestic price setting in favour of commercial negotiation; and amendments to controls on monopsonic acquisition of raw sugar. The Federal Government declined to accept the IAC's recommendations. However, following this inquiry, a number of government initiated reviews led to several changes to the regulatory arrangements for the industry.

In 1985, the Sugar Industry Working Party agreed to the general thrust of IAC's previous recommendations and recommended changes to regulations governing cane growing, cane pricing, raw sugar acquisition and marketing. As summarised by the Boston Consulting Group (1996) , "following this report greater flexibility was introduced into grower/miller relations, and there was a general increase in the application of commercial principles." These changes were legislated through amendments to The Regulation of Sugar Cane Prices Act , in 1986, and implemented with joint support of Commonwealth/State Governments. For example, in 1987, a $100 m Sugar Industry Infrastructure Package was introduced to provide assistance to millers and growers for industry restructuring (Industry Commission, 1992) .

In 1989, the embargo on sugar imports was lifted and an ad valorem tariff at $110 per tonne was introduced. This was followed by changes to pool pricing by the Queensland Government. These significant changes to industry regulation led to further deregulation, and consequent expansion of the Australian Sugar Industry in the 1990's.

The introduction of the Queensland Sugar Industry Act 1991 was a major step towards reorganising the Australian sugar industry to permit gradual expansion of the industry's capacity. Following recommendations of the 1990 Report of the Sugar Industry Working Party (Sugar Industry Working Party , 1990) , the Sugar Industry Act 1991 repealed the old legislation controlling cane growing and sale to mills, and established the Queensland Sugar Corporation to develop and implement policy relating to the management of the Queensland industry. The Sugar Industry Tribunal and the Sugar Industry Policy Council were also established under the Sugar Industry Act 1991 . Despite these changes the core elements of the previous legislation were retained. Notably, the provisions to maintain the assignment system to regulate sugarcane areas and grower-miller relationships, and the compulsory acquisition of all raw sugar for single-desk selling meant that the industry continued to be highly regulated. Hence the Industry Commission noted that "… the Sugar industry is continuing to be one of the most highly regulated industries in Australia" (1992), pp. 36). The Commission continued to push for significant deregulation of the industry in a further report to the Commonwealth Government.

In particular, the 1992 IC report recommended:

- the removal of tariffs on sugar imports in exchange for a single payment to producers;

- the abolition of acquisition except to satisfy long-term contracts; and

- the abolition of assignments from 1995 onwards.

As in 1983, the Commonwealth Government opted not to implement the recommendation of the IC. Instead, a Sugar Industry Task Force was established in 1992 to identify impediments to sustainable growth and competitiveness of the Australian sugar industry and to determine the appropriate level of future government support for the industry. This is the first time that ‘sustainability' emerged as a planning target for the sugar industry development.

The Task Force recommendations resulted in the Commonwealth and Queensland Governments introducing an agreed sugar industry adjustment package in 1993. The package included funding for infrastructure development, maintenance of sugar tariff and reduction of pool price differential from 12 percent to 6 percent. The package also encouraged industry expansion decisions to be made at the mill area level with the continuation of the assignment system.

While these policy changes enabled the Australian sugar industry to respond positively to opportunities that have emerged over recent years from economic developments in Australia and overseas, there has been an extensive program of structural reform within the domestic economy, prompting further deregulation of industry controls. In particular, the Commonwealth Government's micro-economic reform program led to the deregulation of the banking system, abolition of exchange controls and a general reduction of import Tariffs following the successful completion of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement of Tariffs and Trade (GATT). There also has been a major focus on economic reforms on transport, power and public sector agencies in a drive towards adoption of a national competition policy (National Competition Council (NCC), 1996) .

These underlying changes in the policy environment and a sunset clause in the Sugar Industry Act 1991 , led to the formation of the Sugar Industry Review Working Party (SIRWP) in 1996. Following deliberations of the SIRWP, the Australian Government abolished the tariff protection applicable to the Sugar Industry with effect from July 1997 (1997). The tariff was initially set at $110 per tonne and later reduced to $55 per tonne, reflecting an ad valorem tax of around 13 percent on raw sugar and 9 percent on refined sugar imports (Boston Consulting Group, 1996) . Given very low volumes of sugar imports to Australia, the industry did not consider the abolition of the tariff as a significant loss of assistance to the local sugar industry. Rather, the industry employed this as a bargaining device to retain the monopsony acquisition and single-desk marketing arrangements that applies to all raw sugar produced in Queensland (Canegrowers, 1997) . Therefore, under the regulatory system applicable in 1998, cane land assignment system remains a central device of the regulatory structure. Furthermore, with increasing community interest in the environment, augmented by government interest in responding to such concerns, the land assignment system is being promoted as a planning apparatus to address economic and environmental conflicts of sugar industry land use (Mary Maher and Associates, 1996)

Managing these natural resource conflicts involves a complex process, and includes trade-off decisions involving economic, environmental and social objectives. The anecdotal evidence suggests that the capacity of the current assignment process to handle such issues varies substantially across cane growing regions. As noted in Mary Maher and Associates (1996) , "some areas have been active in developing assignment guidelines that incorporate significant local environmental issues". In other areas, private economic interests guide the assignment decisions . Although communities are concerned about the consequences of such dealings, local governments find it difficult to disallow these developments, as they are legitimate ‘as of right' activities on freehold land currently classified under ‘rural pursuits'.

Presented in the next section are the major elements of the assignment system, its operation, and a discussion on some economic and environmental issues related to its continuation.

Introduced initially in 1926, the primary aim of the assignment system is to regulate the commercial growing and harvesting of sugar cane. It is essentially an instrument that binds the grower and the miller in a contractual arrangement that interests both parties. Under this mutually agreed arrangement, an assignment is an entitlement conferred upon its holder to deliver cane to a particular mill for crushing. The mill is obliged to accept cane of an acceptable quality grown on land assigned to it. The grower is obliged to deliver sugarcane to the mill to which the land is assigned.

One important feature of the sugar industry that promotes such binding agreements between the growers and the millers is the role of the miller as a monopsony in the factor market. In any particular cane growing region, numerous growers supply their cane to a single mill (or, a few mills owned and operated by a single interest). While the survival of the mill rests largely on the supply of cane for crushing on a regular basis, without the mill landowners would not be attracted to growing cane. Because of the large number of growers, compared to a single miller, the miller could, in a fully deregulated environment, set prices in a way that would maximise milling profits at a cost to the growers. This would lead to a net transfer of wealth from growers to mill owners. Beard and Wegener (Beard, and Wegener, 1998) addressed this issue in a recent paper.

While such concerns are often well-founded, in the regulated environment that now exists in the Australian sugar industry with controlled monopsonies the only buyers for cane, mechanisms to address many of these inequities are incorporated within legislative controls (Day, 1985) . Efficiency costs of such controls, compared to an unregulated situation, have been the subject of many studies by ABARE and the Industry Commission over past decades ( Bartley, and Connell, 1991 ; Connell, and Borrell, 1987 ; Industry Commission, 1992 ). The Sugar Industry Review Working Party revisited these issues during its deliberations ( Boston Consulting Group, 1996 ; Industry Commission, 1996 ; SIRWP, 1996 ). As SIRWP's preferred position indicates, the balance of the arguments for and against the assignment system favours its continuation at least over the medium term. However, the industry will find it increasingly difficult to retain the current level of regulation beyond the medium term due to the very nature of problems that face a maturing industry. As indicated by Randall (1981) in relation to the Australian water economy, during the expansionary phase the concern is on the appropriate rate of expansion because of the low social costs of expansion. In contrast, the mature phase of industry development is characterised by rising costs. For the sugar industry, these costs relate to land because land prices are driven by more direct and intense competition among different resource users. Greatly increased interdependencies among natural resource users also direct community attention to the social costs of externalities in land use. In this respect, much of the Australian sugar industry is at its mature phase.

Several issues become relevant during the mature phase. First the economic concerns for government assistance will diminish and industry profitability will become a key issue for growth. Factor pricing will become more competitive with greater attention paid to net social costs, in particular, the non-pecuniary implications. Absolute and relative scarcity of cane land, externality problems of intensive farming, and conflicts among different kinds of land users will become increasingly relevant in the coming years for the Australian sugar industry.

Associated with these issues, are many issues that relate to the grower-miller interface. They relate to the overall profitability and viability of existing production arrangements, and capital needs to fund the rehabilitation of the aging milling infrastructure. While the existing regulatory structures are generally been regarded by the industry as being in their best interest, declining profit margins may eventually push the industry toward lifting controls on land allocation to bring about efficiency and equity improvements ( ABARE, 1991 ; Beard, and Wegener, 1998 ). In this respect, potential externality implications of alternative land allocation systems are of immense interest to industry and the community.

The issues surrounding the assignment process, like many other natural resource allocation mechanisms, are multifaceted and hence difficult to analyse using a single criterion. The concept of economic efficiency generally guides public policy decisions. For the most part, the performance criterion is the maximisation of national welfare. Many of the economic analyses undertaken by the national agencies such as the IC (1992) , and various ABARE studies follow this conceptual orientation ( ABARE, 1991 ; Bartley, and Connell, 1991 ).

Economists use a utility function to represent the preferences of individuals. They make deductions based on aggregate behaviour of individuals in the marketplace. It is common knowledge in contemporary resource economics that elements of the physical, economic and social system within which these preferences are expressed act as constraints in determining the final outcome. Therefore, in attempting to manage the efficient use of natural resources, social and environmental aspects of resource use cannot be ignored despite real difficulties associated with handling these trade-offs. Decision-makers who allocate of caneland through the cane assignment system encounter many such trade-offs between economic, social and environmental objectives in land management. Furthermore, the sugar industry's regional concentration, intensive nature of cane farming and vertically integrated system of operations, place the sugar industry in a unique policy setting amongst other Australian farm based industries. The closest comparisons in this respect are the Australian wine grapes industry, canning fruit industry and the dairy industry. However, all differ substantially in their regulatory policy setting; in particular, the lack of it.

Quiggin (1997) reviewed the applicability of three analytical frameworks based on the externality, sustainability and property rights concepts, for the analysis of the impact of using resources in intensive agricultural systems. His analysis concluded that, given the complex nature of problems raised by sugar industry operations, different analytical frameworks may be necessary to address different issues.

SIRWP (1996) identified major elements of the cane assignment system. A cane assignment is an offer of right to grow cane on defined parcels of land, with the linked obligation that the cane so produced must be sold to a particular mill. It therefore provides an assurance on the access to an outlet for the cane grower, and a ready supply of cane for the mill.

The two parties to this agreement, the grower and the miler, are governed by a mill area collective bargaining arrangement. This is implemented through a Local Area Board, which also administers the process for granting and transferring assignment. The process restricts competition between mills for cane supply, because the grower and the miller are operating under a mutual agreement.

Looking closer at the issues indicates that they relate primarily to private, short-term economic interests of the major players, namely the growers and the millers. However, these issues also have direct implications on the long-term economic interests of the industry and the welfare of the general public. Some of the issues of particular concern are the externality effects of production and the sustainability of the natural environment. The fact that access to rights also brings responsibilities on the executor of those rights is often ignored. On the one hand, landholders have a 'duty of care' responsibility to manage their land in a sustainable way. On the other, landholders may have a 'claim' for compensation if they are restricted from enjoying their ownership entitlements. Land clearing for cane growing is an example of conflict related to potential loss to the society of public good benefits associated with private use.

There is no central control over land allocation for cane growing by a state or national level body. The Sugar Industry Act 1991 provides the statutory basis for the operation of the assignment system. Local Area Board, which manages the assignment system, follows the guidelines offered by the Act , and some forms of planning controls imposed by Local Government agencies for land clearing and development. The Local Boards include representation by the growers and the millers, and an independent chairperson to represent community interests. As noted by BCG (1996) , the granting of the assignment requires that "…land may be prepared and utilised for the growing of sugarcane without undue damage to the environment. However, little guidance is offered on what might constitute ‘ undue ' damage (italics added)".

This leads us to several issues of interest. There is prior recognition that conversion of land to cane is potentially ‘damaging' to the environment. The party that seeks assignment is motivated as a rational and self-interested agent to invest in an activity to increase personal wealth. While associated environmental damage may result in a loss of potential private welfare, the net gains associated with receiving the assignment are perceived to heavily outweigh the costs. The extent of these gains, however, is not clearly understood, in particular the public costs arising due to externality implications on the environment. In certain circumstances, there could be a mismatch between individual gains and community losses, for example, habitat destruction. While this uncertainty prevails, it may be possible that, while individuals may gain from the granting of cane assignment, in the case of new land clearing the whole community may value the destruction of habitat as a considerable loss.

There are four elements to be taken into account in the whole equation matching benefits and costs: individual gain (from receiving the cane assignment); individual loss from destruction of habitat; community gain from greater output of sugar; and community loss from destruction of habitat. An important factor bound with uncertainty, which determines the extent of net benefits, is the value that the community places on environmental protection. If the community members outside the sugar industry recognise the value of habitat lost through industry expansion as more important than the extra sugar that is produced from newly-assigned land, then there is a net loss of benefit to the society from further expansion. It is unlikely that the current case-by-case assignment procedures applied to cane assignment can effectively address these significant issues.

Furthermore, the role of the Local Board in managing the granting of new assignments is of interest. Naturally, new assignments can only be granted if there is potentially unused mill capacity. Therefore, it is in the best interest of the miller to allocate the assignment to those potential growers who meet the assignment criteria. The environmental credentials of the potential new growers are of interest to the miller, but only to the extent that they impinge on the reliability of cane supplies to the mill within the planning horizon of the mill operation. In 1998, crushing capacity of mills is a genuine concern in the Queensland Sugar Industry. For example, in the Herbert River District, there is a moratorium on further expansion because of the lack of available mill capacity. In certain other regions, viability of the mill is under threat due to lack of supplies, because more land is being diverted to uses away from cane production. On the one hand, mill owners might use environmental reasons to discourage growers from expanding production in areas with limited mill capacity, while on the other, there is the tendency to push ahead with granting assignments with little regard to environmental issues in areas with supply uncertainty. Both possibilities are important in a social welfare perspective of resource allocation, because it could undermine the long-term sustainability of the industry and the environmental integrity of the natural resource.

Mills themselves are in a difficult situation. They have a dual role: to be good corporate citizens, as well as good financial managers. With their current under-capacity, mill owners are confronted with balancing growers' interests (expand cane assignment), their own financial interest (not increase their debt), and the community interest (restrict caneland expansion). Each of the groups is looking on with their own perspective, and perhaps fails to understand their appropriate position. As suggested by the Australian Sugar Milling Council during SIRWP deliberations, the environmental compliance should be the responsibility of individual assignment holders (SIRWP, 1996) . The general community also supports this view. Canegrowers' tactical response to this is the Code of Practice for Sustainable Cane Growing (Canegrowers, 1998a) . The industry requests individual members to comply with the provisions of the Code. The Code is voluntary, and it is aimed at a general level of compliance within the guidelines available in existing legislation for land clearing, soil conservation, environmental protection and waste management. While most cane growers are expected to comply with the Code, deviation from compliance may most likely result in special conditions, designed to ensure sustainable production being attached to the cane assignment. Availability of appropriate information is an issue that needs addressing to ensure wider compliance.

Moreover, the assignment system is associated with generating ‘concentrated benefits' to the industry, while imposing ‘diffused costs'. The benefits of the assignment system accrue mainly to the established growers. The costs, which include both allocative inefficiencies associated with the assignment process (Wills, 1997) and the externality impacts on the environment, are borne by the industry and the community alike, but are far less transparent. Therefore the independent chair of the Local Boards has a mammoth task to weigh up environmental benefits that have larger public good values from restricting developments, against direct economic benefits of the sugar production activities. While Local Boards are entitled to seek external advice on these matters, and various public and private agencies have the potential to contribute, it is perceived to be "inconsistent with a policy of industry self management ..." (SIRWP, 1996) . Credibility of such arguments for an industry operating in a multi-user environment is worth exploring from a strategic planning viewpoint.

Industry expansion has its share of winners and losers. The primary winners, the sugar industry partners, are regionally concentrated, and in many regions have a significant stake in local decision-making. Yet the relatively large number of losers, the cost-bearers of a regulated industry, are less well organised to form a significant force. Therefore, the industry is likely to exert pressure to maintain its relatively strong position. The industry has a further advantage in pursuing this position, because the economic rents associated with sugar production are relatively large, and the multiplier effects of sugar industry income are significant in cane growing regions. It will be particularly so as long as the true costs of sugar production – in terms of production and externality costs– are not clearly reflected in industry decisions. Therefore, information relating to the trade-offs between economic and environmental values of sugar production is rated highly as a public good, and of strategic importance for a maturing industry.

There is widespread concern that recent expansion in the sugar industry has been on to more marginal lands. The definition of marginal lands is purely a productivity concern in economics. A further important dimension is the extent of the externalities involved in growing cane on lower quality lands. This necessitates the increased use of non-land inputs to maintain productivity. In this respect, the use of appropriate technology to target fertilisers and agrochemicals to effective use, as well as adopting farming systems that keeps externalities within acceptable levels, are opportunities available to achieve a sustainable sugar cane industry (Canegrowers, 1998a ). Analysing these issues at a regional level can produce strategic information to guide efficient allocation decisions that balance the efficiency and equity issues confronted by the stakeholders.

There is also some concern within the industry, and in other circles, that some existing areas of productive cane land are being transformed to other non-agricultural uses (Walker, and Johnson, 1996) . Just as Sugar Industry participants pursue their interests to gain access to good quality land for sugar production, it is natural for other developers to seek opportunities to maximise wealth generation through non-farm activities. In an unrestricted market, it is the willingness-to-pay for the services offered through such developments, that dictates the level of such transformations. The issue, however, is that market failures are commonplace in many cane growing regions. This is largely due to asymmetries in access to information, and hence the desired outcomes of the free economic activity are not fully achievable. For example, as the balance of economic activity in regional centres where sugar production has been a principal activity changes, there are growing opportunities for recreation, urban development and life-style interests, such as ‘hobby farming'. Whether these developments are of broader community interest, or just satisfy the needs of a few individuals are some questions facing regional communities.

It is understood that both farm and non-farm development activities diminishes the area of open space that provide for the preservation of species, the provision of clean water and other goods and services which have the characteristics of public goods. Further, the activities carried out in developed areas have the potential to contribute to the degradation of existing public good aspects of the open space. Both the diminishing area of open space, and the declining quality of the available open areas, increase the values placed by society on the preservation of land resources with amenity value.

Behind these issues is the question of the nature of institutional structures that might be used to achieve an improved allocation of land with an increasing population and a desire to improve living standards. Moreover, mutually acceptable solutions to resolve conflicts that surround land assignment within the industry have important implications for the economic viability of the industry, the ecological integrity of natural resources and the well being of regional communities.

Sustainable development and sustainability are notorious for having a vast range of definitions, but in formal analysis they can be regarded as binding constraints that prevent the adoption of management strategies that lead to a reduction in the stock of ‘natural capital' (Pezzey, 1997) . However, in practice these constraints are ignored in the decision process, or become only distantly relevant. I support the argument that the notion of sustainability can be viewed as a unified principle of justice between contemporaries, and between present and future generations (Howarth, 1997) . In terms of an achievable policy objective for resource management, minimising externalities is an appropriate goal.

This view encompasses both spatial and intertemporal externalities of production. An institutional framework that pays adequate attention to the property rights concept is likely to provide appropriate mechanisms for the achievement of sustainability objectives. The nature of production externalities, and the seemingly conflicting private and public interests associated with sugar industry operations, suggest that the current rights structure is ill defined. There are opportunities for collective negotiation to arrive at more equitable and effective means of allocating these rights.

Randall (1991) and Randall and Farmer (1994) promote the idea of linking economic efficiency criteria with a safe minimum standard of conservation to achieve the objective of sustainability. MacAulay (1996) extends the notion of safe minimum standard to the use of legally binding covenants to restrict the productive use of resources when there are externality issues involved. Although these restrictions are meant to ensure sustainability of the resource base beyond the current generation, they are regarded overly conservative and inconsistent with the notion of Pareto efficiency. However, we also cannot overlook the issues of rights and fairness that are essential to political economy (Howarth, 1997) , particularly under a decentralised decision making environment. This is applicable to natural resource management in contemporary Australia. The intuitions behind safe-minimum standards and the precautionary principle can only be made operational through carefully defined rights and obligation structures for individuals seeking access to resource use. The Canegrowers' Environmental Code of Practice encompasses this notion. However, its effectiveness will rest largely on the extent of economic-environmental trade-offs involved in adapting the code by individual canegrowers. Therefore, in attempting to influence regional resource allocation decisions, it is helpful to analyse these trade-offs following an optimising framework adapted to accommodate spatially distributed constraints (Pezzey, 1997) .

A question often raised is "Do markets generate incentives for resource conservation sufficient to ensure the welfare of future generations?" The answer to this question in the context of the Australian Sugar Industry is, "Perhaps, no"; because the Sugar Industry operates in a regulated setting on the one hand, while on the other, a major competitor for land use in the region, the environment, has no formal market. Resource allocation conflicts inevitably arise under such circumstances, and there is a need for other mechanisms to resolve the conflicts in a manner consistent with changing societal values.

Within the communities in the sugar producing regions there is interest in using information-based technology to identify land suitability for alternative uses. SIRWP (1996) endorsed such sentiments by proposing greater use of resource information to aid assignment decisions. Therefore, there is scope for employing safe-minimum standard type rules within a planning context to encourage socially desirable land uses. These minimum criteria must be based on scientific knowledge on resource suitability, and reflect growing knowledge on the environment, and changing community attitudes to environmental protection.

Given the wide range of stakeholders involved in land use planning in sugar growing regions, there will always be a tendency for conflicts to arise because the goals of some stakeholders will inevitably be unachievable. Conflicts over environmental management are due partly to differences in goals, and the way goals are characterised by individuals ( Rogers, and Sinden, 1994 ). These conflicts relate to three interconnected issues: the value of resources, carrying capacity of resources and the trade-offs between alternative uses for resources. Development of rules for resolving conflict in land use issues thus needs to be based on a robust framework that can handle these complexities. In particular, multiple objectives in resource use. Given the range of objectives encountered, there is the need to compare values for all resource use options, including those related to public good uses for which established markets do not exist.

There are two general approaches to the assessment of values associated with natural resource use and management: benefit-cost analysis (BCA) and multi-criteria analysis ( Conway, 1991 ; McAllister, 1982 ; Van Den Bergh , and Nijkamp, 1991). MCA is gaining recognition as an effective tool to address problems related to natural resource allocation (Romero, 1996) . MCA can encompass a range of value expressions, but does not readily discriminate between them. Benefit cost analysis, on the other hand, assumes a particular structure of values based on exchange preferences (Lockwood, 1997) . Over the years, BCA has been criticised for its weaknesses, in particular its inability to consider distributional consequences. Nevertheless, its suitability as a tool for strategic decision making is well regarded. It is considered an "exceptionally useful framework for consistently organising disparate information" and thereby "improve the process and, hence, the outcome of policy analysis" (Arrow et al. , 1996) . In particular, the extended cost-benefit analysis takes into account those costs and benefits that are not directly observable in the market place, and have a high relevance to assessing natural resource management issues.

It is desirable to develop an integrated approach that improves the efficacy of the BCA approach for strategic resource assessment (Lockwood, 1997) . The aim is to combine the values and expectations of the stakeholders interested in Sugar Industry developments, with the bio-physical information on the resource endowment, to assess the trade-offs between economic and environmental objectives for sugar industry development. This follows the notion that effective integration of environmental and social constraints within the decision-making process permits elicitation of relative valuations of private and public goods. Full information decisions that incorporate externality and transaction costs associated with alternative land use options can provide the basis for efficient allocation of scarce natural resources.

It is questionable whether the existing mechanisms for resource allocation in the expanding sugar industry follow well-defined procedures that meet rigorous public accountability criteria. The Assignment and Mill Area Negotiation Process that specifies the interface between the cane grower and the miller does not follow a uniform approach across cane growing regions (Boston Consulting Group, 1996) . This is particularly true for the assessment of public good aspects of the allocation.

The potential of these mechanisms to identify and elicit values in ways that can help stakeholders understand the implications of a particular decision is uncertain. They fail to properly account for the impact of decisions, and to assess the extent of trade-offs involved in competing options. Failure of such policies is characterised by their inability to provide robust insights to guide long-term resource allocations. Therefore there is a need to develop effective mechanisms to analyse alternative land-use scenarios in a transparent manner. There is a growing volume of literature suggesting multiple use management as a practical approach to maintain ecological integrity and sustainability of natural systems adapted for productive purposes. Issues related to regional economic efficiency, such as economies of scale, institutional arrangements, and logistic concerns of the industry seem to suggest that dominant use management (Ward, and Lynch, 1997) ( or management of regional resources in a way that suits the dominant industry), may be an efficient option for the sugar industry. To assess these arguments, it is necessary to develop a strategic regional resource appraisal procedure (SRRA) to investigate a range of options to find the best practicable options (Bond, and Brooks, 1997) .

As with any other rural industry, the finite supply of farmland implies that the expansionary phase of the sugar industry will inevitably come to an end. Industry will reach this equilibrium situation when it is no longer profitable to develop available land for sugarcane, or when the proportion of assigned land that leaves the industry equals that entering the industry in any given year. Current regulatory arrangements might delay this autonomous adjustment process, as it hinders the formation and transmission of appropriate market signals. Delaying this adjustment may mean that the industry could contribute an unsustainable level of externalities through inappropriate production practices, and the resource allocation within the industry remains socially suboptimal. This will lead to increased costs to resource users – including the industry, and to consumers who pay for industry output.

Industry adjustment can be facilitated by the use of appropriate economic instruments in conjunction with legal instruments such as covenants or planning controls. Martin (Martin, 1990) proposed the idea of a "tradeable assignment system" to overcome the deficiencies of the assignment system as it then was. Since 1991, the assignment system has been made more flexible with transfer of assignments allowed within grower's own land holdings, between growers and between mill areas. To exploit the benefits associated with such flexibilities, a market for assignments is required. It could function in a manner similar to the market for irrigation water rights in the southern states. Separating the land title from the rights to grow cane for commercial harvesting will help generate appropriate valuations for land in terms of its productivity.

In the medium to long-term, such a system will discourage expansion of sugarcane production on to marginal land and will have positive consequences for the environment. On one hand, positive land valuations will encourage good resource stewardship: poor land managers will be penalised in the market place, because such a market will reflect the cost of externalities associated with land use. For example, a grower who resorts to sustainable land improvements, such as having a healthy riparian zone that harbours predatory birds – such as owls that control rats on cane fields, will likely to receive higher prices for land. On the contrary, a grower who establishes a farm on a property known to have problem soils such as acid sulphate soils will most likely have a very low potential sale value. Potential buyers will be diverted from it due to the high externality costs it produces. Also, as a consequence, the demand for cane assignments on problem soils will diminish, and cane production will eventually be limited to those soils which are most appropriate for sustainable cane production. Therefore, such a system may eventually lead to a more efficient management of land within the industry, with cane output levels and production costs reflecting the potential of the resource to produce cane. This would also clarify some uncertainties associated with investment in cane transport and milling infrastructure, and encourage investment to enhance farm productivity.

Operation of such a market, will benefit from an institutional framework that supports efficient cane growers and discourages those who cause externality costs and reduce overall industry efficiency.

Formulation, development and implementation of these policy guidelines, planning controls and operational rules for the sugar industry development require systematic consideration of policy implications on the multiple stakeholders. For example, those growers who practice the code of practice may receive higher premiums in the market. Similarly those who have riparian vegetation may see their costs in terms of lost cane being recouped in terms of higher land values. But, if higher land values were to raise growers tax burden imposed through higher rates, then the policy would likely to become counter-productive. An incentive structure, such as rate rebates being developed for riparian land on farm properties, will address such anomalies and will have significant social benefits (Canegrowers, 1998b ). Effective policy must balance the objectives of industry developers and the conservation interests in a socially equitable manner. Policies need to be transparent and unambiguous to be effective; but they need to be flexible to permit innovation and enterprise. A SRRA procedure offers a robust framework to conduct such assessments and to identify best practicable options.

The foregoing discussion suggests that the Australian Sugar Industry is faced with a complex range of economic, environmental and social conflicts related to its expansion. The Industry needs effective mechanisms to address its long term resource allocation problems. Such problems are not limited to the land assignment issue. However, the land assignment system is the primary instrument that directs and regulates the industry expansion at present. It establishes the interdependency between the cane growing and sugar processing sectors. It creates benefits to individuals but it also creates opportunities for them to create environmental costs. However, these costs do not become apparent to those who bear it, because of the vertically integrated nature of the operations and the relatively high levels of profitability associated with cane growing. However, they become important in a social perspective because inefficiency mean lost welfare from the use of resources. Therefore it is desirable to attache more stringent conditions to assignments when they are granted so that they do not inadvertently create undue environmental costs, some of which also impart direct costs to canegrowers in terms of lost productivity on cane farms.

Following Bromley (Bromley, 1991) , property represents streams of benefits. Property rights, or rights to access such streams of benefits, also carry associated obligations or social duties. Resource use conflicts in a multi-user environment are the result of disagreements related to those rights and duties and benefit streams that represent ‘property' to various interests. Definition of clearly specified property rights in cane assignments in conjunction with land use controls based on land suitability criteria would provide an efficient institutional framework to address some adjustment issues in the sugar industry. Others, in particular those that relate to contemporary and intertemporal externalities, indivisibilities and irreversibilities require broader policy analysis that includes the consideration of the dichotomy between collective choice and private interest.

The sugar industry has not had to consider the wishes of the broader community in the past, because the industry created significant regional benefits and the environment was not a social priority. The community objectives to natural resource use and management has changed considerably over the past decade, and environmental sustainability is an established community goal enshrined in government policy. In a finite world with multiple resource users, meeting sustainability objectives requires a robust understanding of the contributions of economic activities and environmental amenities to social well-being (Dodds, 1997) . The solutions must evolve within biophysical realities and broader community welfare objectives. In this respect, information based on scenario development and interpretation using systematic procedures at a broader scale than the individual management unit can contribute to the debate on how to organise land use activities within a region.

ABARE, 1991 , The Australian Sugar Industry in the 1990s, Submission, ABARE, Canberra.

Arrow, K. J. , Cropper, M. L., Eads, G. C., and others 1996, 'Is there a role for Benefit-Cost Analysis in environmental, health, and safety regulation?', Science , vol. 272, no. April 12, pp. 221-222.

Bartley, S. W ., and Connell, P. J., 1991, Impacts of regulatory changes on sugar growers, ABARE Discussion Paper, AGPS, Canberra.

Beard, R. M ., and Wegener, M. K., 1998, Effect of deregulation in the Sugar Industry on the Price of Sugarcane, 42nd Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Armidale, NSW, 19-21 January.

Bond, A. J ., and Brooks, D. J. 1997, 'A strategic framework to determine the best practicable environmental options for proposed transport schemes', Journal of Environmental Management , vol. 51, pp. 305-321.

Boston Consulting Group , 1996, Report to the Sugar Industry Review Working Party: Analysis of issues & identification of possible options, Boston Consulting Group, Sydney.

Bromley, D. W ., 1991, Environment and economy: property rights and public policy , Basil Blackwell, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Canegrowers 1997 , 'Sugar industry puts tariff in perspective', Australian Canegrower , vol. 19, no. 12, pp. 5.

---, 1998a, Code of practice for sustainable cane growing, Canegrowers, Brisbane, Queensland.

--- 1998b, 'Rates cut for growers who protect the bush', Australian Canegrower , vol. 20, no. 19, pp. 22.

Connell, P. J ., and Borrell, B., 1987, Costs and Regulation of Cane Harvesting Practices, BAE Occasional Paper, 101, AGPS, Canberra.

Conway, A. G . 1991, 'A role for economic instruments in reconciling agricultural and environmental policy in accordance with the polluter pays principle', European Review of Agricultural Economics , vol. 18, pp. 467-484.

Day, K . 1985, 'Growers fear exploitation by millers', Australian Canegrower , vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 8-9.

Dodds, S . 1997, 'Towards a 'science of sustainability': Improving the way ecological economics understands human well-being', Ecological Economics , vol. 23, pp. 95-111.

Howarth , R. B. 1997, 'Sustainability as opportunity', Land Economics , vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 569-79.

Industry Commission , 1992, The Australian Sugar Industry, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

---, 1996, Submission to the Sugar Industry Review Working Party, AGPS, Canberra.

Johnson, A. K. L., McDonald, G. T., Shrubsole, D., and others, 1997, Sharing the land: The sugar industry as a part of the wider landscape, Keating, B. A., and Wilson, J. R., ed., Intensive Sugar Cane Production: Meeting the Challenges beyond 2000, 1996.

Kerr, B 1997, 'Queensland Sugar Industry Retains its best Features - An Assessment of the Australian Government Working Party's Review', International Sugar Journal , vol. 99, no. 1178 February, pp. 66-67.

Lockwood, M . 1997, 'Integrated value theory for natural areas', Ecological Economics , vol. 20, pp. 83-93.

MacAulay , T. G., 1996, A role of covenants in markets for natural resources, Contributed paper to the 40th Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, 1-16 February.

Martin , W. 1990, 'Public choice theory and Australian agricultural policy reform', Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics , vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 189-211.

Mary Maher and Associates, 1996, Environmental Issues and the Assignment System, Boston Consulting Group, Sydney, Australia.

McAllister, D. M., 1982, Ealuation in environmental planning: assessing environmental, social, economic and political trade-offs , The MIT Press, Massachusetts and London.

McKinnon , W. A., 1983, The Sugar Industry, Industries Assistance Commission report , 332, AGPS, Canberra.

National Competition Council (NCC), 1996, Considering the Public Interest Under the National Competition Policy, NCC, Canberra.

Pezzey , J. C. V. 1997, 'Sustainability constraints versus "Optimality" versus Intertemporal Concern, and Axioms versus data', Land Economics , vol. 73, no. 4, pp. 448-466.

Queensland Department of Environment and Heritage, 1995, Conservation of the Mahogany Glider Petaurus gracilis, Conservation Plan Series, S95/0359, QDEH, Brisbane.

Queensland Department of Primary Industries, 1995, Situation Analysis of the Queensland Sugar Industry, QDPI, Brisbane.

Quiggin , J., 1997, The Economics of Resource Use and Environmental Impact in Intensive Agricultural Systems, Keating, B. A., and Wilson, J. R., ed., Intensive Sugar Cane Production: Meeting the Challenges beyond 2000, 1996.

Randall, A., 1981, Property entitlements and pricing policies for a maturing water economy: Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics , v. 25, no. 3, pp. 195-220.

--- 1991, 'The economic value of biodiversity', Ambio: A Journal of the Human Environment , vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 64-68.

Randall, A., and Farmer, M. C., 1994, Benefits, costs and a Safe Minimum Standard of conservation Bromley, D. W., ed., Handbook of Environmental Economics, Blackwell, London.

Rogers , M. F., and Sinden, J. A. 1994, 'Safe minimum standard for environmental choices: old-growth forest in New South wales', Journal of Environmental Management , vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 89-103.

Romero , C. 1996, 'Multicriteria Decision Analysis and Environmental Economics - An Approximation', European Journal of Operational Research , vol. 96, no. 1, pp. 81-89.

SIRWP , 1996, Sugar - Winning Globally: Report of the Sugar Industry Review Working Party, QDPI, Brisbane.

Sugar Industry Working Party , 1990, Sugar Industry Working Party Report, Sugar Industry Working Party , Brisbane.

Van Den Bergh , J. C. J. M., and Nijkamp, P. 1991, 'Operationalizing sustainable development: dynamic ecologoical models', Ecological Economics , vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 11-13.

Walker , D. H., and Johnson, A. K. L. 1996, 'Delivering Flexible Decision Support: A Case Study in Integrated Catchment Management', Australian Journal of Environmental Management , vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 174-188.

Ward , F., and Lynch, T. P. 1997, 'Is dominant use management compatible with basin-wide economic efficiency?', Water Resources Research , vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 1165-1170.

Wills , I., 1997, Should governments act to preserve caneland? A critical review, Johnson, A. K. L., Robinson, I. B., and Wegener, M. K., eds., Coastal Queensland and the Sugar Industry: Land Use Problems and Opportunities, Pan Pacific Hotel, Gold Coast, January 20 1997 , SRDC Technical Report No. 1/97.

|